I’m pleased to report that last week held a number of highlights, two of which pertained to this column. The first was a surprise package in our mailbox. To be more precise, it was a clear plastic bag that contained three time-yellowed newspaper clippings and a cryptic Post-it note. The articles were from the 1953 Evening Citizen, the late afternoon edition of the Ottawa Citizen. They were installments in a “Valley Towns” series that a young reporter by the name of Fred Inglis was doing on rural towns and villages up and down the Ottawa valley. Somehow Mr. Inglis stumbled across Dunvegan — you have to remember that this was 20+ years before the 417 — and added it to his list of communities in the spotlight. His original plan had been to devote two columns to Dunvegan. However, he ended up writing four. And, by his own admission, he collected enough material to pen a fifth. As you will see over the next few weeks, the series provides a very interesting snapshot of this once vibrant locale. My intention is to share highlights from this “Valley Towns” series over the next four weeks. I will also post the full articles on my blog: Dunvegan-Times.ca.

The second column-related highlight arose from the first. As astute readers will have noted, I only received three of the articles in a four-part series. One was missing. Numero uno, in fact. I searched in vain to find it in an on-line database. In its drive to corner the genealogical research market with Ancestry.com and Newspapers.com, the alphabet gang has bought up as many North American digitized newspaper archives as it can. They hold the Ottawa Citizen files but, regrettably, they are incomplete. So, I contacted the Ottawa Public Library. They not only had back issues on file, one of their librarians took it upon herself to search for the missing article from July 7, 1953 and then email it to me… all within hours of my original inquiry. Impressive. By way of contrast, I also reached out to Library & Archives Canada and simply asked if they had back copies of the Evening Citizen. Seven days later I am still awaiting a reply.

Before we look at what Mr. Inglis uncovered in his visit 68 years ago, I wanted to thank the kind person who dropped off the three newspaper clippings. I have no idea who the contributor was; the enclosed note simply said “No sign of No. 1!” If he or she reads this, I wanted to express my gratitude.

Valley Towns: part 1

Fred Inglis was native of Vancouver. He served with the RCMP before joining the armed forces during WW II. Fred was transferred to Ottawa in the early 1940s. I don’t know what his duties were but, after the war, he settled in the capital and joined the Ottawa Citizen in 1946 as a reporter, which could be a clue to how he spent his wartime years. To quote from his obituary, “(he) was well-known for a series of features he wrote in the 1950s on the Ottawa Valley.” In the first of the four-part feature he wrote on Dunvegan, he paints a picture of a far more vibrant settlement than the sleepy husk of a hamlet that exists today. As you read his words, try to put yourself in his shoes and see Dunvegan as it once was.

“This tradition-steeped, Highland-founded hamlet in Glengarry County was once a large and thriving village. If its industries of 50 or 60 years ago were here today, you could have your logs cut into lumber, your grain milled into flour and grist, your hides tanned, shoes made and wool woven Into blankets. While your wife was shopping or buying a new hat at one of the many stores, you could have a bracer at the hotel. While your horses were being shod you would probably call at the tinsmith, cabinet shop or carriage and wagon shop. Today, at the four corners of Dunvegan, you have two stores, a garage, a cheese factory, a church, a school and an Orange Hall. There is a small seed cleaning plant and a part time weaver… Dunvegan is about 65 miles east of Ottawa by way of Plantagenet and St. Isidore. It’s about six miles west of Highway 34 that takes you to Alexandria, Vankleek Hill and Hawkesbury. Four miles west is a paved road that runs past the former home of Ralph Connor and on to Maxville and Highway 43. The closest railway is the CNR at Greenfield five miles south… Dunvegan was settled by Highlanders from the Isle of Skye and from Glenelg, on the Scottish mainland. These strong men and brave women made their homestead in what were then virgin forests. They came here around 1832 and named their community after Dunvegan in their native land… Most of these early settlers spoke only Gaelic. They conducted their church services in Gaelic and their business in English. Many of their descendants — the older folks — still speak fluent Gaelic when they get together. In the Presbyterian Church, Dunvegan’s only church, they hold a traditional ‘old time’ service In Gaelic once a year… They don’t need any street signs here, but an early map of the village shows Church street, running north and south, past the church; Main Street, east and west; Hamelin Street, Alice and Polly Streets. Dunvegan has produced many doctors and clergymen and for many years had a resident physician. They speak here of Baltic’s Corners, named for John MacLeod who served on the Baltic Sea; of Big Kate’s Hill, of Little Annie, of Cripple Dick, the shoemaker; of ‘Billy D.’ MacRae who owned the cheese factory for over 40 years; of W. D. W. ‘Little Willie’ MacLeod who brought in 1,500 pounds of milk. They tell of celebrating Bannock Night; of the late Pipe Major Johnnie Alex Stewart, the blacksmith. Like its neighboring village of Maxville, Dunvegan has many ‘Mac’s,’ descendants of Scottish pioneers; such names as MacCrimmon, MacLeod, MacSweyn, MacIntosh, MacRae, MacKinnon and MacDonald. Other family names still here are Dewar, Urquhart, Fleming, Stewart, Ferguson, Chisholm and Campbell.”

I think the locals of 1953 might have been pulling Fred’s leg a wee bit. I’m not convinced there was gristmill in Dunvegan. Or a carriage shop, for that matter. But who knows. He was in the enviable position of interviewing elderly residents who were only a few generations downstream from the original settlers.

Have truck, will travel

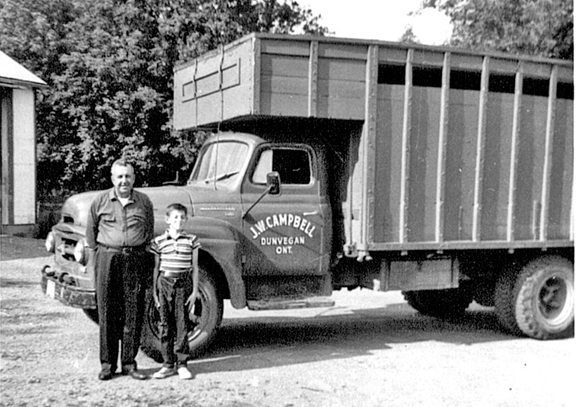

One of the Dunvegan businesses that Mr. Inglis seems to have missed in his 1953 feature is James W. Campbell’s droving business. It was an easy mistake. Jimmy Campbell had no sign, no storefront and no workshop. The only outward indication of Campbell’s enterprise was that one of the doors of his two bay shed was oversized. Mr. Campbell operated one of those “a man and his truck” businesses. Only he wasn’t helping people move their household goods, he was moving farm animals: to and from auction sales, from farm to farm or to a slaughterhouse. I’m told that Jimmy learned the droving trade as the driver of a cattle truck for drover Donald Duncan McKinnon. Donald D. lived in Dunvegan in the first house east of the Orange (now DRA) Hall. His brother, Wally, ran the sawmill that was located just a wee bit east of where the Glengarry Pioneer Museum is today. As so few of Dunvegan residents today have any connection to agriculture, it’s probably worth taking a minute to explain what a “drover” is. One dictionary defines a drover as one who drives cattle or sheep to market or one who buys livestock in one place to sell in another. It’s a honourable trade that dates back for millennia.

Until the invention of the truck in the 20th century, drovers traditionally worked on foot driving “droves” of cattle, hogs, sheep and even geese and turkeys from the countryside to markets in urban centres. It was a system based solely on trust. A farmer didn’t have time to make the long trip to the marketplace and back. So he would entrust his livestock to a drover to care for his animals on the journey to market and reliably bring back the proceeds. In Great Britain, it’s estimated that by the end of the 1700s nearly a million cattle and sheep were being driven on foot to London. The rapid expansion of the British rail system put an end to most droving in that country around the mid 1800s.

Back here in Canada, Jimmy bought a used ½ ton truck, built a large covered stock box on the back, had his name lettered on the doors of the cab and he was in business, almost. The key to the droving business was P.C.V. or Public Commercial Vehicle operating license. It granted the holder the exclusive right to provide a transportation service (droving for example) within a specified territory. For the most part, Jimmy transported livestock and feed to Montreal. Although looking through his account books I noticed that he also made trips across the border to Vermont. Whenever he could, he would also look for loads that he could back haul to Dunvegan. Some farmers would have him pick up bagged fertilizer, or metal from the Montreal scrapyards for a building project.

Jimmy Campbell operated his droving business for over 40 years, until ill health forced him to step aside and let his son Robert take over in 1988. Robert Campbell operated the family business for ten years until, like his father, health issues forced him to sell the truck and hang up his drover license. However, as Robert explained to me, the time had come to throw in the towel. The droving business was in rapid decline. Auction sales were closing, abattoirs were being shuttered left and right and there were a lot fewer farms. From a high of 700,000 farms in Canada in 1941, by 2016 the total was only 200,000. And, in 2016, the family farm looked nothing like its 1940s predecessor in terms of sales and size. Average acreage per farm had gone from 225 acres in 1941 to 800 in 2016.

Robert no longer has a drover’s truck. And both bay doors on the shed behind his family home across from the museum are normal size garage doors. However, if you look carefully, you’ll spot the opening that’s been filled in where Robert’s dad used to park the 1944 used truck (serial #1411) he bought in December of 1947 from Graham Creamery for $2,859.

-30-